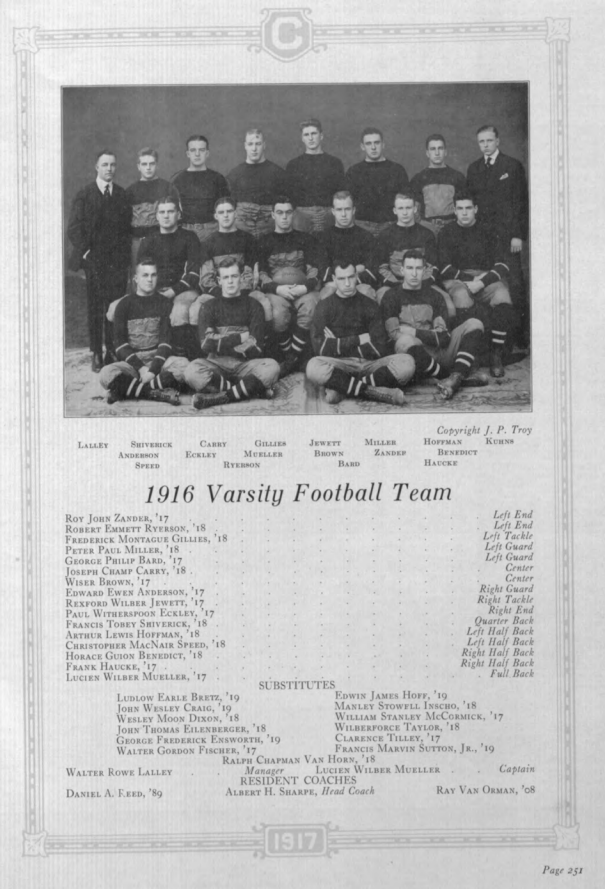

Review of the 1916 Football Season

The Cornell football team of 1916, though making a creditable showing, failed to keep up the championship pace set by its illustrious predecessor, the unbeaten team of 1915. However, it must be said that the 11 was of the same powerful, finished type which has characterized the efforts of Dr. Sharpe since the firm establishment of his regime in Ithaca. Eight games were played, of which, Cornell won all but two, defeating Gettysburg, Williams, Bucknell, Michigan, the Massachusetts Aggies, and Carnegie Tech., and losing to Harvard and Pennsylvania. Cornell scored 165 points to her opponents’ 73. In four of the games, the opposing team was shut out; in two, there were close scores; and in two Cornell was decisively beaten.

Unfortunately, for the development of the team, an outbreak of infantile paralysis in the East caused the university authorities to postpone the opening of college for two weeks. As a result, the first game, which had been scheduled with Oberlin, was canceled and practice was delayed for a week. It was not until Monday, September 25, that Coaches Sharpe, Reed, and Van Orman began work with a squad of about 55 men. The outlook was not unfavorable despite the late beginning. It must be admitted that the coaches faced the rather discouraging task of replacing three of the greatest stars in Cornell’s gridiron history, Barrett, Cook, and Shelton, quarterback, center, and left end on the 1915 championship team. Collins, the brilliant halfback and Jameson, one of the most dependable forwards that Dan Reed has turned out in years, were also lost through graduation. Yet there remained much promising material among the veterans of the past season and among the substitutes who played on the second team. THere were Captain Mueller, fullback; Shiverick, right half; Eckley, right end; Miller, left guard; Anderson, right guard; Gillies, left tackle; all of whom had played on the 1915 varsity team, and Tilley, a guard of several years’ varsity experience.

The season opened with the Gettysburg game on Monday, October 9, which resulted in a Cornell victory with the score of 26 to 0. Naturally the team was rather crude at this early stage; it was lacking in speed and efficient team play, but it showed considerable evidence of possessing latent power. The line showed up well, but although the line bucks were stopped almost without exception, the ends proved to be vulnerable. Shiverick was seen for the first time at quarterback while Hoffman and Benedict were the halfbacks. In the last period, Speed was sent in to give the signals and Shiverick took Benedict’s place.

On the following Saturday, October 14, the weak Williams team was overwhelmed by the score of 42 to 0. The victory may be attributed chiefly to superior physical strength, for although the line showed up well and the backfield seemed to work in harmony, the ends proved once more to be exceedingly weak. Eckley and Zander were both out of the game, and so the choice for ends fell on Ryerson and Eilenberger. Pennington and Ensworth were also tried out in this position. In the backfield, Bretz appeared to have the making of a brilliant player, and Haucke and Speed also showed up well as substitute backs. Among the line substitutes, Dixon and Fischer were conspicuous for good playing. The team had not yet received a real test, for the Purple’s opposition was very ineffective.

Then followed on October 21, the game with Bucknell. Cornell was victorious, but the showing of the team was not so encouraging as on the previous Saturday. Serious weaknesses in team and individual play were revealed. Perhaps on account of its late start, the 11 was still slow; it lacked ginger, its end play had not materially improved and its backfield, while powerful, failed to show speed and punch.

The playing of the team in the Harvard game at Cambridge where it was defeated 23 to 0, was a great disappointment to the thousands of Cornellians who had gathered from many places to see the game. Harvard’s superlative skill which showed itself in effective punting, aggressive line work, and persistent ability to follow the ball, was the reason for defeat. The Cornell backs were unable to hold the ball and were lacking skill in picking their openings. Eckley broke into the game for the first time of the season but both he and Zander were tricked and boxed by the Harvard interference. Fumbling and weak defensive line work which forced Shiverick to hurry many of his kicks, were other characteristics of Cornell play at Cambridge.

Two of Harvard’s touchdowns came as a direct result of fumbling. Shiverick’s fumble of a punt near the end of the first period gave the ball to Harvard on the Cornell 35-yard line. A forward pass, unmolested by Cornell, took the ball to the 17-yard line where on the first play of the second quarter Casey shook off the whole Cornell 11 and scored the first touchdown. The last Harvard touchdown was even more of a gift. Cornell had stopped the Harvard rushes and gained the ball on her own seven-yard line when Haucke, who had been substituted for Hoffman, juggled the ball right into the arms of Sweetser, the Harvard left tackle, enabling him to cross the goal line for the final score.

On their return to Ithaca the players set their teeth and went quietly to work. By the time of the game with Carnegie Tech., which Cornell won by the score of 15 to 7, the team already showed an improvement in individual play, yet it was plain that it had not regained its stride. Loose tackling and slow thinking coupled with poor work on the part of the ends allowed Carnegie to make many long gains which were discouraging to those who believed that the team could come back after its defeat at the hands of Harvard. Speed started the game instead of Shiverick until the final period when the latter took his place and the former displaced Hoffman. At this point in the game the team seemed to awaken a bit from its lethargy and it advanced the ball with comparative ease.

But the Cornell football team of 1916 “found itself” on the following Saturday, November 11. With the stand on Schoellkopf Field packed with 12,000 spectators, Cornell defeated Michigan in what was perhaps the most thrilling game seen in Ithaca in many years. At first, Cornell led but then Michigan came up from behind and at the end of the first half, the score was 20 to 6 in her favor. A long forward pass thrown by Peach and caught by Dunne repeated several times led to two touchdowns, and Michigan’s end runs and off tackle rushes found little resistence. At this point, it seemed that Michigan was in every respect the superior team. The Michigan men were fast and in every play, whereas the Cornell interference was utterly ineffective. But in the last 20 minutes of the game it was a different story. The Cornell team began to think and play a brand of football that was irrestible. It could not be driven out of Michigan territory. If Shiverick was forced to kick, the team stopped Maulbetsch and Smith in their vain attempts to gain. The line broke through time and again and hurried the Michigan punter so that his kicks soared high into the air. And so, with the aid of Shiverick’s wonderful kicks, the Cornell offense crossed Michigan’s goal line twice, making the score 20 to 20. Though there was not much longer to play both teams fought bitterly to break the tie which seemed inevitable. Sparks, who was now playing quarterback for Michigan, rushed the ball to Cornell’s 10-yard line, but Cornell held for downs and brought the ball back to the 28-yard line. Here Shiverick executed a remarkable punt which sailed over the heads of the Michigan backs and came to rest on the three-yard line. Michigan punted to her own 30-yard line and after three scrimmages had gained seven yards, Shiverick stepped back and kicked his third field goal.

Still the seemingly interminable second half was not ended. Cornell kicked off and Michigan tried pass after pass without success until the final whistle blew.

The team closed the local season on the following Saturday by defeating the Massachusetts Agricultural College 37 to 0. The field was completely watersoaked, and the ground was so slippery that neither team played good football. Shiverick didn’t play, and his place was taken by Speed who punted well, and ran the team with good judgment. The halfbacks were Hoffman and Van Horn. Captain Mueller played throughout the first half and Fischer substituted for him at fullback for the rest of the game. Cornell’s real defensive strength was not tested, for the visitors made only three first downs in the whole game and Cornell had the ball most of the time. The condition of the field was such that in spite of little opposition, the backs usually took four downs to gain the ten yards.

Nine days later 24 members of the squad left for Atlantic City, there to remain until the morning of Thanksgiving Day. They were Captain Mueller, Anderson, Eckley, Jewett, Shiverick, Gillies, Miller, Carry, Speed, Hoffman, Ryerson, Eilenberger, Sutton, McCormick, Brown, Bard, Taylor, Zander, Fischer, Haucke, Benedict, Tilley, Dixon, and Van Horn. Before the men were the three successive victories of preceding years, 21 to 0, 24 to 12, 24 to 9.

In the final game, Pennsylvania with an excellent team, coached to take advantage of the weaknesses which Cornell had been displaying all season, was victorious by the score of 23 to 3. Cornell’s fatal weakness was in the line, and it is difficult to understand why five men who had played against Penn in the previous year should fail to stop their lighter opponents. As a consequence, the backfield was unable to make substantial gains, and Shiverick was hurried in his punting. Two of his kicks were blocked and one of these blocked kicks was directly converted into a touchdown. Again, forward passing was made difficult by the fact that Pennsylvania players continually sifted through the line.

Pennsylvania had a varied attack in which a deadly and well executed forward pass was especially effective. In ability to gain ground by rushing, Pennsylvania had much the better of Cornell. Penn gained about 200 yards from scrimmage—about twice as much as Cornell. The victory was won not by overwhelming strength, but by better maneuvering, greater resourcefulness, and more readiness to seize opportunities.

The only bright spot in the game for the large Cornell representation at Franklin Field was the first few minutes of play. Matthews made a poor kick-off, and Cornell got the ball near mid-field. After gaining by an exchange of punts, Shiverick kicked a field goal. The Cornell stock fell almost at once, however, when Penn scored her first touchdown, yet hope did not die out for a victory until the second half when the longed-for Cornell rally which had made itself famous in the Michigan game failed to materialize. Thus ended the season of 1916.

The 1917 squad should find many veterans eligible to play as well as a large number substitutes with considerable experience. There will be Shiverick, Speed, Benedict, and Bretz in the backfield, Ryerson, Eilenberger, and Ensworth at the ends, and Gillies, Miller, and Carry in the line. The team loses by graduation Captain Mueller, Eckley, Zander, Brown, Anderson, Tilley, Bard, Haucke, and Fischer.